Testi e video didattico

Il Santo Sepolcro di Leon Battista Alberti

nella Firenze del Quattrocento

21 Aprile – 6 Giugno

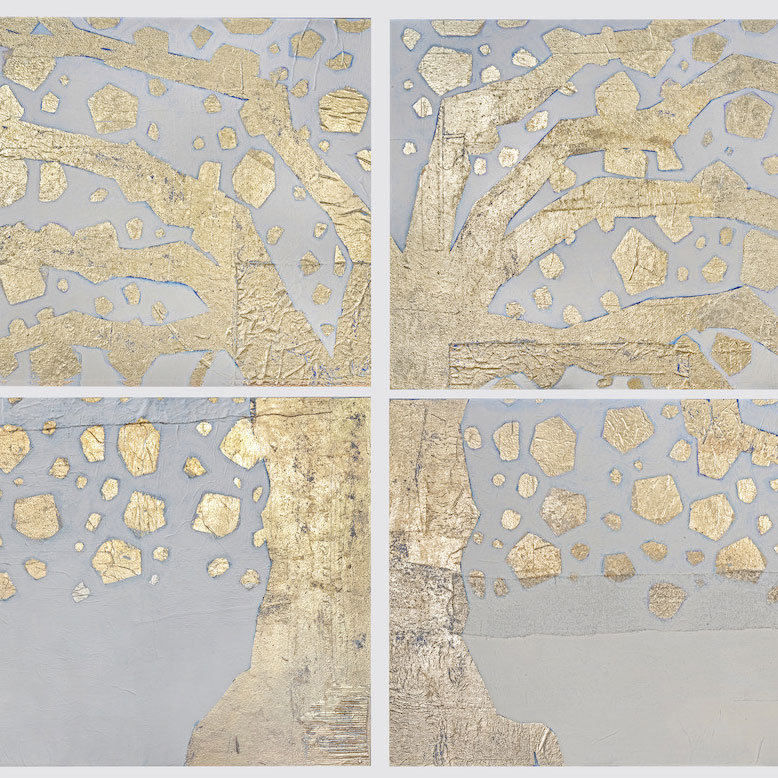

Nell’occasione del convegno Rinascenza e Risurrezione e della mostra d’arte sacra contemporanea Fons Vitae, promossi dall’Ufficio d’Arte Sacra dell’Arcidiocesi di Firenze, di concerto con la Facoltà Teologica dell’Italia Centrale, questo racconto didattico è stato elaborato nel Museo Marino Marini in prossimità al Sepolcro, per suggerire il senso dell’opera dell’Alberti nella Firenze d’allora, che vedeva nel rinnovamento della cultura antica un segno del trionfo pasquale di Cristo.

I luoghi del Sepolcro

Il Sepolcro fu realizzato nella Cappella Rucellai, sul fianco nord dell’antica chiesa di San Pancrazio, documentata dal 931 e tra i templi che il cronista trecentesco Giovanni Villani ritenne fondati da Carlo Magno. A partire dal 1230 San Pancrazio con l’attiguo monastero furono affidati ai benedettini vallombrosani, i quali ingrandirono la chiesa nel XIV secolo e tra il 1447-56 rifecero il chiostro, contiguo con il Palazzo Rucellai rinnovato dall’Alberti. Il disegno della Cappella Rucellai e la realizzazione del Sepolcro sono quindi il prosieguo dei lavori del chiostro.

La prima idea del committente prevedeva un’altra collocazione: la Cappella Rucellai del transetto est di Santa Maria Novella, la cui facciata sarebbe stata infatti completata per volere di Giovanni di Paolo sul progetto di Leon Battista Alberti negli stessi anni del Sepolcro in San Pancrazio. Il cambiamento di destinazione fu forse dovuto alla scelta del committente di farsi seppellire vicino ai suoi antenati in San Pancrazio.

Il committente

Giovanni di Paolo Ruccellai (1403-1481), per l’intensa attività costruttiva noto come ‘Giovanni delle fabbriche’, fu un mercante di stoffe fiorentino e autore dello Zibaldone Quadragesimale, una collezione di testi riguardanti la vita della sua famiglia e la storia fiorentina. Nel 1428 sposò Jacopa Strozzi, figlia del ricchissimo Palla, il rivale di Cosimo Vecchio, ma non fece mai parte della fazione anti-medicea capeggiata dagli Strozzi. E nel 1466, quando il Sepolcro era quasi ultimato, Giovanni riuscì a legare la sua famiglia ai Medici, sposando il figlio Bernardo con la nipotina di Cosimo Vecchio e sorella di Lorenzo il Magnifico, Nannina de’Medici: un legame di parentela ricordato nel Sepolcro da tre imprese medicee: quella di Cosimo, quella di suo figlio Piero e quella del nipote Lorenzo “il Magnifico”. Amico personale di Leon Battista Alberti, Giovanni ebbe da lui i progetti per il Palazzo e per la Loggia Rucellai, nonché per il completamento della facciata di Santa Maria Novella e per il Sepolcro; alla morte nel 1481 fu sepolto in San Pancrazio, nel pavimento della cappella, tra il Sepolcro e l’altare.

L’architetto

Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), figlio naturale di Lorenzo Alberti, membro dell’importante famiglia fiorentina, esiliata per motivi politici a partire dal 1388, scelse presto la carriera ecclesiastica, anche come sostegno per i suoi variegati interessi umanistici. Nato a Genova, dopo gli studi a Padova, Venezia e Bologna diventò nel 1431 segretario del Patriarca di Grado, e poi, a Roma nel 1432, ‘abbreviatore’ della Curia Pontificia, ricevendo la prebenda della Pieve di San Martino a Gangalandi a Lastra a Signa, vicino a Firenze, e poi di quella di Borgo San Lorenzo.

Al seguito di Papa Eugenio IV ebbe modo di conoscere Firenze nel 1434 e di lì a breve scrisse il trattato De pictura, in cui parla dell’arte contemporanea, menzionando per nome Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, Masaccio e Luca della Robbia. Difensore del volgare, tradusse il proprio trattato latino, dedicando la versione italiana, Della pittura, al Brunelleschi. Archeologo, architetto, medaglista e teorico scrisse testi fondamentali anche sulla scultura e sull’architettura.

Nella sua qualità di latinista della cancelleria papale, nel 1438-39 Alberti partecipò alle sedute ferraresi e fiorentine del Concilio convocato per riappacificare le chiese d’Oriente con la Chiesa Latina. Dopo il Concilio tornò col papa nella Città Eterna dove, intorno al 1450, stilò una Descriptio urbis Romae nella quale ricostruiva la topografia dell’antica capitale. Il Santo Sepolcro è uno dei progetti del ventennio 1450-70 in cui questa cultura antiquaria dell’Alberti è decisiva.

L’occasione

Alberti e Rucellai si erano conosciuti negli anni del Concilio, probabilmente negli ambienti di Santa Maria Novella, dove si svolgevano le sessioni conciliari e dove era alloggiato il seguito di Eugenio IV, nel cosiddetto ‘Appartamento Papale’. I Rucellai avevano il patronato di una importante cappella nella basilica dei domenicani, e l’idea di erigervi una replica del Santo Sepolcro nasce in questo periodo, parallelamente al progetto di completamento della facciata della stessa basilica. Ambedue i progetti sembrano perciò collegati, nel loro nascere, all’agognato risanamento della divisione tra cristiani orientali e occidentali: la facciata avrebbe commemorato il Concilio dell’Unione, mentre il Sepolcro ne avrebbe celebrato il risultato più clamoroso, la riconquista militare dei Luoghi Santi gerosolimitani per gli sforzi uniti di Greci e Latini.

Ma l’unione decisa dal Concilio non fu accettata dalle chiese d’Oriente, e quando la facciata e il Sepolcro furono finalmente avviati negli anni Cinquanta fu con altre finalità: la prima come generoso dono di ‘Giovanni delle fabbriche’ alla sua città, e il secondo come segno della fede personale del committente cinquantenne, che ormai pensava alla propria sepoltura. Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai voleva giacere nella chiesa di famiglia, San Pancrazio, e così le due opere, concepite per stare insieme, vennero separate.

Il significato originale non fu tuttavia dimenticato, perché negli anni di realizzazione dell’uno e dell’altro progetto un altro toscano, il papa senese Pio II, cercò di organizzare una crociata per riprendere i Luoghi Santi, definitivamente perduti con la conquista ottomana di Costantinopoli nel 1453.

L’aspetto originale del sacello

In San Pancrazio il Sepolcro si presentava in modo assai diverso da quanto vediamo oggi. La cappella in cui sorgeva non si apriva su quella contigua, come ora, ma verso la navata della chiesa. Al posto dell’attuale parete sud, realizzata nel 1808 quando l’autorità napoleonica ridusse la chiesa a sede della Lotteria Imperiale, Alberti aveva praticato un varco di sei metri di larghezza, sorretto dall’architrave classicheggiante e dalle colonne successivamente trasferite alla facciata esterna della chiesa. Dice il Vasari: “Fece Leon Battista in San Brancazio una cappella che si regge sopra gli architravi grandi, posati sopra due colonne e due pilastri”. Per chi guardava dalla navata, il Sepolcro in stile antico, così diverso dall’architettura trecentesca della navata, invitava a vedere nella risurrezione del Salvatore un principio di rinnovamento, come se l’architettura proclamasse, con Cristo risorto: “Io faccio nuove tutte le cose” (Ap 21,1-5).

L ’esperienza religiosa

Per chi accedeva invece dalla piazza – dalla porta particolare (poi murata) –, due iscrizioni comunicavano il senso religioso del Sepolcro, al contempo universale e personale. Sulla facciata ovest, dirimpetto alla porta, le parole, YHESUM QUAERITIS scolpite nel cornicione – ‘Voi cercate Gesù’ -, equiparavano la visita di devozione all’antico pellegrinaggio dei cristiani ai luoghi santi. Puntali di ferro tra gli acroteri della cimasa servivano a sostenere dei ceri che, accesi, creavano intorno al Sepolcro un clima di orazione.

Girando attorno poi, l’iscrizione continua: NAZARENUM CRUCIFIXUM SURREXIT NON EST HIC ECCE LOCUS UBI POSUERUNT EUM. Il testo intero riporta cioè le parole dell’angelo alle donne venute al Sepolcro la mattina di Pasqua: “Voi cercate Gesù il Nazareno crocifisso. È risorto, non è qui. Ecco il luogo dove l’avevano messo” (Mc 16,6). Non a caso, sull’absidiola del Sepolcro – a est, sopra la botola del sepolcreto e davanti alla posizione originale dell’altare – l’iscrizione riporta le parole che spiegano l’importanza mistica del Sepolcro: NON EST HIC, “Non è qui”. Gesù il Nazareno crocifisso e poi risorto non è nel Sepolcro. E’ questa la fede di tutti i cristiani, incluso Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, seppellito sotto queste parole.

Tornando alla facciata ovest del Sepolcro, si incontra infine la porticina d’ingresso al luogo santo, dove una targa informa che: “Giovanni Rucellai figlio di Paolo, onde ottenere la sua salvezza là dove con Cristo avvenne la risurrezione di tutti, curò che fosse costruito questo sacello sul modello del Sepolcro di Gerusalemme. 1467”. All’interno un affresco nel timpano della parete est raffigura Cristo morto, e un altro, più grande, sopra la lastra del sarcofago, Cristo che risorge. Qui come nell’originale struttura gerosolimitana, il sarcofago serviva anche da altare per la Messa.

Testimonianze parallele

Nella Firenze quattrocentesca l’utilizzo dell’architettura all’antica in situazioni riguardanti la morte di Cristo o del singolo cristiano era diffuso. Negli stessi anni in cui il Sacello albertiano prendeva forma, vari artisti realizzavano la sontuosa cappella funebre del Cardinale di Portogallo a San Miniato al Monte, e nella basilica di San Lorenzo, Donatello dava forma classica al Sepolcro del Pulpito della Risurrezione, nella scena delle pie donne alla tomba la mattina di Pasqua. Tale associazione dell’‘antico’ con l’‘eterno’ era iniziata negli anni Venti, con il tabernacolo classicheggiante dipinto da Masaccio intorno al Cristo in croce sostenuto dal Padre che gli dà lo Spirito, nella Santissima Trinità di Santa Maria Novella, e nell’architettura brunelleschiana della cappella funebre dei genitori di Cosimo Vecchio, detta Sagrestia Vecchia, a San Lorenzo. Anche l’area funebre di Onofrio Strozzi, nella sagrestia di Santa Trinita, riproponeva elementi classici – un sarcofago all’antica sotto un arcosolio -, aggiungendo un rimando alla morte e risurrezione di Cristo nella pala d’altare dirimpetto all’arcosolio, la Deposizione del Beato Angelico con scene della Risurrezione nei pinnacoli eseguiti da Lorenzo Monaco. In modo analogo gli splendidi cibori eucaristici di Michelozzo alla Santissima Annunziata, a San Miniato e a Impruneta ‘situavano’ il sacrificio di Cristo – reso presente nella Messa – tra colonne, modanature e trabeazioni all’antica.

Rinascenza come Risurrezione

Il Quattrocento fiorentino si è infatti servito del redivivo stile antico come immagine del trionfo di Cristo sulla morte, affrescato dentro il Sepolcro da un alunno di Piero della Francesca. La Pasqua è infatti interpretata come un ‘trionfo’, e un noto inno liturgico – Victimae paschali laudes – saluta il Risorto come Victor Rex, “Re vincitore”; un altro inno descrive come triumphans pompa nobili, victor surgit de funere – “il vincitore sorge dalla tomba, celebrando il nobile trionfo”. L’inno del Vespro di Pasqua insiste ancora: Consurgit Christus tumulo, victor redit de barathro, tyrannum trudens vinculo et paradisum reserans – “Cristo sorge dal tumulo, il vincitore torna dal baratro, spezzando le catene del tiranno e riaprendo il Paradiso”. Pochi anni prima del Sepolcro albertiano, il pittore Andrea del Castagno aveva immaginato il Risorto proprio così: un giovane eroe vittorioso, e così anche Piero della Francesca.

Credenti, Alberti e Rucellai conoscevano questi testi cristiani, e umanisti, conoscevano l’“Exegi monumentum” del poeta pagano Ovidio—l’impulso a celebrare sé stessi con un “monumento perenne”. Così, in un’epoca in cui si leggeva la Bibbia in latino, si ricordavano che la Vulgata designa il Sepolcro di Cristo precisamente con la parola “monumentum”, come anche il responsorio dell’Ufficio cantato il Sabato Santo: “Sepulto Domino, signatum est monumentum”, “Sepolto il Signore, viene sigillato il monumento”. Hanno quindi fuso le due accezioni del termine – quella classica e quella evangelica – in una lettura ‘monumentale’ del Sepolcro del Victor Rex Gesù. Per i cristiani infatti la sua Pasqua dischiude il senso di ogni trionfo sul male e sulla morte.

Fiorenza, la natura risorta, il battesimo

Anche gli elementi non classici del Sepolcro albertiano alludono alla Pasqua. Gli acroteri gigliformi collegano ‘Fiorenza’, l’antica Florentia, “città in fiore”, con la primavera, la stagione in cui Cristo tornò dalla morte alla vita. La stessa sensibilità ‘cosmica’ viene illustrata nella coeva Vita di Cristo dell’Armadio degli Argenti del Beato Angelico, dove le scene dell’Orazione di Gesù nell’orto e del Compianto sul Cristo morto abbondano di alberi in fiore e fiori per terra, associando l’imminente Risurrezione con l’annuale rinascita della natura. Troviamo il simbolismo della tomba fiorita anche nel monumento funebre del vescovo Benozzo Federighi, realizzato da Luca della Robbia appena tre anni prima del Sepolcro albertiano, dove i gigli e le rose della cornice in terracotta policroma si stagliano dal marmo bianco-grigio del monumento stesso. La tomba del Federighi, oggi in Santa Trinita, nel Quattrocento si trovava in San Pancrazio, a pochi metri dal Sepolcro dell’Alberti.

Soprattutto, la bicromia bianco-verde del Sepolcro albertiano, d’ispirazione non antica e romana ma medievale e fiorentina, allude alla Pasqua. Rievoca i rivestimenti di San Miniato al Monte – il santuario di un martire raffigurato come risorto -, nonché del Battistero, al cui interno i mosaici mostrano i morti che risorgono sotto i piedi del Risorto. Per la teologia cristiana, il sacramento del battesimo è infatti partecipazione alla morte e alla risurrezione del Salvatore, secondo il ragionamento di san Paolo: “Per mezzo del battesimo, dunque, siamo stati sepolti insieme a lui nella morte, affinché, come Cristo fu risuscitato dai morti per mezzo della gloria del Padre, così anche noi possiamo camminare in una vita nuova” (Romani 6, 3-4).

Rucellai, che come tutti i fiorentini d’allora era stato battezzato in San Giovanni, ha forse voluto, lui, il richiamo visivo al luogo in cui era ‘rinato’ sacramentalmente? Sia a San Miniato che al Battistero, poi, vi è lo stesso abbinamento di paraste ‘all’antica’ e tarsie bianco-verdi di cui Alberti si serve nel Sepolcro: un’alternanza di elementi classicheggianti e di bicromia che l’artista stava allora utilizzando nell’altra grande commissione di Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, ovvero la facciata di Santa Maria Novella, completata tre anni dopo il sacello di San Pancrazio.

On the occasion of the scholarly conference Renaissance and Resurrection, and of the exhibition of contemporary Christian art Fons Vitae, promoted by the Sacred Art Office of the Archdiocese of Florence together with the School of Theology of Central Italy, this didactic exhibit has been mounted in the Marino Marini Museum, near the Sepulchre, to suggest the meaning of Alberti’s masterpiece in the Florence of his time, which in the renewal of ancient culture saw a sign of Christ’s paschal triumph.

The Places of the Sepulchre

The Sepulchre was realized in the Rucellai Chapel, on the north side of the church of San Pancrazio, documented from the year 931 and one of the churches that the 14th-century chronicler Giovanni Villani believed to have been founded by Charlemagne. In 1230 San Pancrazio and the attached monastery were entrusted to the Benedictines of Vallombrosa, who in the 14th century enlarged the church and between 1457-1456 rebuilt the cloister, which is contiguous with the Rucellai palace, redesigned by Alberti a few years earlier. The design of the Rucellai Chapel and the realization of the Sepulchre thus continuations of the rebuilding of the palace and cloister.

But the patron’s first idea was for a different location: the Rucellai Chapel in the east transept of Santa Maria Novella, the church whose façade would later be completed at the behest of Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai and to a design provided by Alberti in the same years as the San Pancrazio Sepulchre. The change of destination was perhaps due to the patron’s choice of San Pancrazio for his own burial site, near the tombs of his ancestors.

The Patron

Giovanni di Paolo Ruccellai (1403-1481), known as ‘Giovanni of the big buildings’ because of his intense activity as a builder, was a Florentine cloth merchant and author of the Zibaldone Quadragesimale, a collection of texts on the life of his family and the history of Florence. In 1428 he married Jacopa Strozzi, daughter of the wealthy Palla Strozzi, rival of Cosimo (the Elder) de’Medici, but never joined the anti-Medici faction lead by the Strozzi. And in 1466, when the Sepulchre was almost finished, Giovanni succeeded in binding his family to that of the Medici by marrying his son Bernardo to Cosimo de’Medici’s grand-daughter, Nannina, the sister of Lorenzo the Magnificent: a family bond made clear on the Sepulchre, which has the personal emblems of three of the Medici: Cosimo, his son Piero and his grandson Lorenzo ‘the Magnificent’. A personal friend of Leon Battista Alberti, Giovanni had the architect design the Rucellai palace and facing loggia as well as the facade of Santa Maria Novella and the Sepulchre. At his death in 1481 Giovanni di Paolo was buried in San Pancrazio, in the pavement of the family chapel, between the Sepulchre and the altar.

The Architect

Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), illegitimate son of Lorenzo Alberti, of the important Florentine family exiled for political reasons in 1388, early chose a career in the Church, in part to sustain his variegated humanistic interests. Born in Genoa, after student years in Padua, Venice and Bologna, in 1431 became secretary to the Patriarch of Grado and then, in Rome in 1432, brief-writer in the Papal chancellery, receiving in benefice the parish church of San Martino a Gangalandi, at Lastra a Signa, near Florence, and later that of Borgo San Lorenzo.

Part of the entourage of Pope Martin V, Alberti came to know Florence in 1434, and shortly afterwards wrote the treatise De pictura, in which he speaks of contemporary art, mentioning by name Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, Masaccio and Luca della Robbia. A defender of the vernacular, Alberti translated his treatise, dedicating the Italian version, Della pittura, to Brunelleschi. Archaeologist, architect, medallist, and theoretician, he also authored basic texts on sculpture and architecture.

In his capacity as Latinist of the Papal Chancery, in 1438-39 Alberti took part in the Ferrarese and Florentine sessions of the Council called to bring about peace between the Eastern Christian Churches and the Church of Rome. After the Council he returned with the Pope to the Eternal City where, around 1450, he wrote a Descriptio urbis Romae reconstructing the topography of the ancient capital. The holy Sepulchre is one of his projects of the years 1450-70 in which Alberti’s antiquarian culture is most evident.

The Occasion

Alberti and Rucellai met in the Council years, probably at Santa Maria Novella, where the council sessions were held and the entourage of Eugenius IV was lodged in the so-called ‘Papal Apartments’. The Rucellai family had the patronage of an important chapel in the Dominican basilica, and the idea of erecting in it a replica of the Holy Sepulchre was born at this time, along with the idea of completing the basilica’s facade. The two projects thus seem to be related, in their initial phase at least, to the longed-for healing of the divisions between Eastern and Western Christians: the façade would have commemorated the Council of Union, while the Sepulchre would have celebrated the most clamorous result of the re-established union, military reconquest of the Holy Places in Jerusalem through the united efforts of Greek and Latin forces.

But the Union desired by the Council was not finally accepted by the Eastern Churches, and when work began on the façade and the Sepulchre in the 1450s it had other objectives. The façade became a generous gift of ‘giovanni of the big buildings’ to his native city, and the Sepulchre a sign of the faith of its patron, who, at fifty years of age, was already thinking of his burial site. Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai wanted his tomb in the family church, San Pancrazio, and thus the two works, conceived to be part of a single whole, were separated.

The original meaning was not lost, however, since the years in which both projects were realized are the same in which another Tuscan, the Sienese pope Pius II, sought to organize a crusade to reclaim the Holy Places, definitively lost with the Ottoman conquest of Jerusalem in 1453.

The Rucellai Chapel’s Original Appearance

In San Pancrazio the Sepulchre had a rather different impact than what we see today. The chapel in which it stands was not open on the neighbouring one, as it is today, but on the nave of the church. In place of the present south wall, put up in 1808, when the Napoleonic government transformed the church into the seat of the Imperial Lottery, Alberti had opened a six-metre wide passage, sustained by the classical architrave e columns later transferred to the church’s external façade. Vasari says: “In San Brancazio Leon Battista made a chapel supported by grand architraves, which rest on two columns and two pilasters”. For all who saw it from the nave, the Sepulchre in ancient style, so different from the 14th-century style of the rest of the church, was an invitation to see the Saviour’s resurrection as a principle of renewal, as if, together with the Risen Christ, the architecture proclaimed: “I make all things new” (Ap 21,1-5).

The Religious Experience

For those entering from the small square in front of the church and using the dedicated portal (later sealed with masonry), two inscriptions communicated the Sepulchre’s religious meaning, at once universal and personal. On the structure’s west front, facing the portal, the words YHESUM QUAERITIS carved in the cornice – “You are seeking Jesus” – made visits of devotion ideally equivalent to the time-honoured Christian pilgrimage to the Holy Places. Iron spikes between the acroteria above the cornice supported candles which, when lit, created a climate of prayer around the Sepulchre.

Moving around the structure, the inscription continues: NAZARENUM CRUCIFIXUM SURREXIT NON EST HIC ECCE LOCUS UBI POSUERUNT EUM. The entire text consists of the words spoken by the Angel to the Holy Women who came to the Sepulchre on Easter morning: “You are seeking Jesus the crucified Nazarene. He has risen, he is not here. This is the place where they had put him” (Mark 16,6). Not accidentally, on the Sepulchre’s apse – at the east end, above the access to the underground burial area and facing the original position of the altar – the inscription cites the words that explain the Sepulchre’s mystic importance: NON EST HIC, “He is not here”. Jesus the crucified Nazarene who rose from the dead is not in the Sepulchre. This is what all Christians believe, including Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, buried beneath these words.

Returning to the west front of the Sepulchre, we finally stand before the structure’s low entry, where a plaque informs us that “Giovanni Rucellai, son of Paolo, in order to obtain his own salvation there where the resurrection of all men was realized with Christ, had this shrine built on the model of the Jerusalem Sepulchre. 1467”. Inside the Sepulchre a fresco in the tympanum of the east wall depicts the dead Christ, and another, much bigger, above the stone sealing the sarcophagus, shows him rising from the dead. Here, as in the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the sarcophagus was used as an altar for Mass.

Similar Messages

In 15th-century Florence the use of ancient architecture in situations related to the death of Christ or of the single Christian was widespread. In the very years in which Alberti’s Sepulchre took shape in san Pancrazio, at San Miniato al Monte several artists were creating the sumptuous funerary chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal, and in the Basilica of San Lorenzo Donatello gave classical form to Christ’s sepulchre in his Resurrection Pulpit, in the scene of The Holy Women at the Tomb on Easter Morning.

The association of ‘ancient’ with ‘eternal’ had begun in the 1420s, with the classical aedicule painted by Masaccio around Christ on the cross supported by God the Father who gives Christ his Spirit, in the Holy Trinity fresco in Santa Maria Novella, and in the funeral chapel of the parents of Cosimo the Elder de’Medici – the ‘old sacristy’ – at San Lorenzo. In the same years the funerary zone of Onofrio Stozzi, in the sacristy of Santa Trinita, used classical elements – a sarcophagus beneath an arcosolium – , adding, right in front of the arcosolium, Fra Angelico’s Deposition of Christ beneath scenes of the resurrection painted by Lorenzo Monaco. In like fashion, Michelozo’s magnificent Eucharistic ciboria at the Santissima Annunziata, San Miniato and Impruneta ‘situated’ Christ’s sacrifice amid columns, mouldings and trabeations in the ancient style.

Renaissance as Resurrection

The Florentine Fifteenth Century used the revived ancient style as an image of Christ’s triumph over death, frescoed within the Sepulchre by a pupil of Piero della Francesca. Easter is in fact interpreted as a ‘triumph’, and a well-known liturgical hymn – Victimae paschali laudes – salutes the Risen Saviour as Victor Rex, “Victorious King”; another hymn describes how triumphans pompa nobili, victor surgit de funere – “the victor rises from his tomb, celebrating a noble triumph”. The Easter Vespers hymn further insists: Consurgit Christus tumulo, victor redit de barathro, tyrannum trudens vinculo et paradisum reserans – “Christ rises from the tomb, the victor from the pit, breaking the tyrant’s chains and re-opening Paradise”. A few years before Alberti’s Sepulchre, the painyeer Andrea del Castagno had imagined the Resurrected Chtrist in just this way, as a victorious young hero, and so too Piero della Francesca.

Believing Christians, Alberti e Rucellai would have known these liturgical texts, and, as humanists, they would have known the “Exegi monumentum” of the pagan poet Ovid—the impulse to celebrate oneself with a “perennial monument”. Thus, in an age in which people still read the Bible in Latin, they would have remembered that the Vulgate designates Christ’s sepuulchre with the very term “monumentum”, as does the responsory of the sung office of Holy Saturday: “Sepulto Domino, signatum est monumentum” – “The lord is buried, the monument is sealed”. And they fused the two uses of the term – the classical one and the Christian one – in a ‘monumental’ reading of the sepulchre of the ‘victorious King’, Jesus. For Christians, his Easter victory discloses the sense of every triumph over evil and death.

Florence, Nature Resurrected, Baptism

Even the non-classical elements of Alberti’s Sepulchre allude to Easter. The lily-shaped acroteria connect ‘Florence’, the ancient Florentia or ‘Flowering City’, with the Spring, the season in which Christ returned from death to life. The same ‘cosmic’ sensibility transpires in the contemporary Life of Christ in Fra Angelico’s Armadio degli Argenti, where the scenes of Christ’s Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane and the Lamentation Over the Dead Christ abound in flowering trees and plants, associating the Saviour’s imminent resurrection with the yearly rebirth of nature. The symbolism of a flowering tomb is also part of the funerary monument of Bishop Benozzo Federighi, realized by Luca della Robbia barely three years before Alberti’s Sepulchre, where the lilies and roses of the polychrome terracotta frame stand out from the grey-white marble of the monument itself. Federighi’s tomb, which today is in the church of Santa Trinita, in the 15th century was in San Pancrazio, just metres distant from Alberti’s Sepulchre.

Above all the white and green marble decoration of Alberti’s Sepulchre, inspired not by ancient Rome but by medieval Florence, alludes to Easter rebirth. It evokes the wall sheathing of San Miniato al Monte, the sanctuary of a martyr saint depicted as risen from the dead, and of the Florence Baptistery, inside which mosaics show the dead rising at the feet of the Risen Christ. For Christian theology, the sacrament of Baptism is in fact participation in the Saviour’s death and resurrection, according to Saint Paul’s reasoning: “By means of Baptism, therefore, we have been buried with him in death, so that – just as Christ was raised from the dead by means of the Father’s glory, so we too can walk in a new life” (Romans 6, 3-4).

Did Rucellai, who – like all Florentines of his time – had been baptized in the Baptistery, himself request this visual recall of the place where he had ‘risen from death’ sacramentally? Both at San Miniato and at the Baptistery there is the same combination of ancient-style pilasters and white-green marble inlay that we see in the Sepulchre: an alternation of classical elements and medieval decoration that the artist used in the same years in Giovanni di Paolo’s other great commission, the façade of Santa Maria novella, completed three years after the Sepulchre at San Pancrazio.

Rinascenza come Resurrezione

Il Santo Sepolcro di Leon Batista Alberti nella Firenze del Quattrocento

Renaissance as Resurrection

Alberti’s Holy Sepulchre in 15th-century Florence